Scripture: Psalm 146, Luke 16:19-31

I live in a home with 84 vacuum cleaners. And I don’t believe for one second that this is by accident.

Vacuum cleaners are one way my son, Noah, makes sense of this world. And as the world doesn’t make very much sense these days, why wouldn’t we just roll with it as his parents?

And roll with it, we have. When I worked in New York and D.C., colleagues who took on foreign assignments would sometimes bring the vacuum they were leaving behind into my office. “See what Noah can do with that,” they’d say. Lugging full-size vacuum cleaners home on the Downtown 1 or the D.C. Metro during rush hour made me Mr. Popular.

He has climbed on and off of school buses with vacuums. I once got a call to pick Noah up from Oxford High School not because he was sick, or in trouble… but because the baseball coach had asked Noah to fix the industrial-sized vacuum they use to clean the team’s indoor practice facility. We had to figure out how to cram the damned thing into the back of our Subaru.

In living with autism, Noah’s journey has been less than conventional. But because nearly everyone has one, vacuum cleaners have helped Noah to connect with others and the world in ways he may not have been able to understand otherwise. Once, when he was perhaps 8 or 9 years old, he struck up a conversation with our young and attractive waitress at a restaurant in New York’s East Village. “Oh, I don’t remember what kind of vacuum I have but it doesn’t work,” she told him. “I could come over and fix it, if you want?” He said with a boyish grin, the one I now can tell usually means he’s attracted to someone.

“I tried the vacuum line a few times,” a friend of mine later joked. “Mixed results.”

But with Noah, whose identity, purpose, meaning and vocation all revolve around these machines we use nearly universally, vacuums are part and parcel to identity. It is how he recognizes others, and how others recognize him. For Noah, vacuums are more than machines. Even with a condition that comes with many challenges in engaging others, vacuums level the playing field of social interaction so he can connect across nearly any difference. There is always an opportunity to connect with others because of the simple fact that we are universally human, created by God to see one another, to name one another, and to love one another - not as we hope someone will be, but as they are.

***

It was common in the age of Jesus for mothers to choose the name of their children based on the circumstances of their birth. In some parts of the world, that’s still the case. I’ve had the joy of sitting with mothers around the planet who have described for me the nature of naming their children. One mother near the Ethiopia - Sudan border brewed delicious, locally harvested and roasted coffee for my colleagues and I during a roadside break as she described for me the circumstances of her children’s births; how earth’s moon, stars and weather led to names for her children.

The name Lazarus means “whom God has helped.” It’s a product of the Hebrew name “Eleazar” (אלעזר), which combines the words for God (ʾEl) and “to help” (ʿazar). Perhaps this Lazarus in Jesus’ story was helped in birth by God - but his life seems devoid of any divine intervention whatsoever.

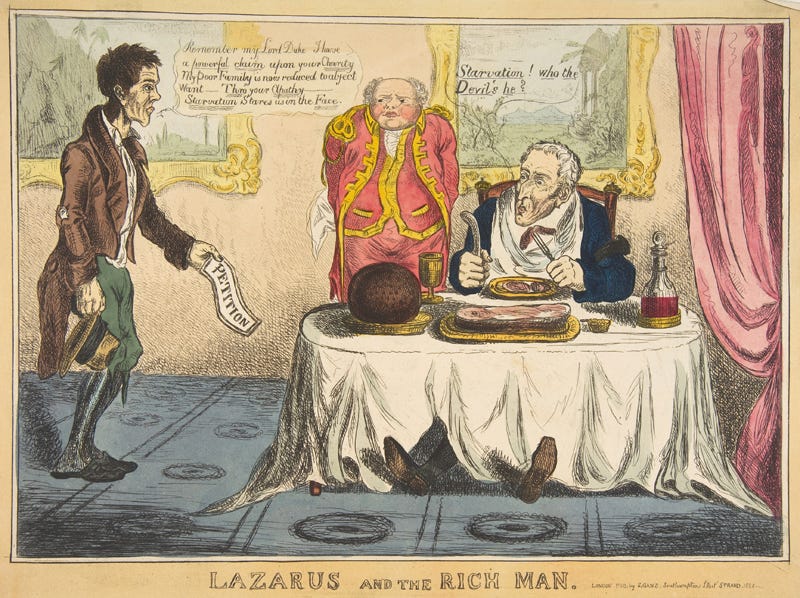

This Lazarus isn’t the same as the one whom Jesus loved in friendship, grieved in death and raised from the dead. This Lazarus is one who many would overlook, someone “...who longed to satisfy his hunger with what fell from the rich man’s table; even the dogs would come and lick his sores.”

He’s someone who likely had a hard time connecting with others, you might say. And yet, the wealthy man has no name in this story but the beggar gets a sacred promotion. The person of power and privilege goes nameless while the beggar has a name, and even a name that invokes God’s work in His life. Ironic, isn’t it? The beggar is named while the rich man is nameless?

Yet this is another total reversal for which Luke’s Gospel is known. Luke reminds us that even the world’s forgotten have names known to God. God calls us to see each person, to name them, and to love them as they are.

In Noah’s world, names and vacuums align so that he can know people better. He can tell you the vacuum in the home of each teacher since age 3. He keeps the people in our lives straight by which vacuum they own. It makes going to the store or anywhere else around town an adventure. He knows more people in Oxford than we do. And not only does he know who owns which vacuum when we run into them at the grocery or the hardware store, their chosen vacuum helps him to remember their names.

Calling someone by name is an act of caring.

***

At the University of Oregon, a researcher named Paul Slovic has spent his career studying why people stop caring when there are events of mass suffering. He found that as numbers in disasters, wars and other tragedies get larger and larger, we become desensitised. We have less of an emotional response. And so we’re less likely to take the kind of action needed to stop genocides, or to send aid where scores of people need it.

Slovic’s research shows that conversely, when people know the names, or at least the stories, of an individual suffering, they are more inclined to help. That’s why names matter to God, and to us. God calls us to see each person, to name them, and to love them as they are.

There is so much to be said for calling someone by their name. That we are named so differently and within so many varying contexts should point to a rich and diverse world where there are innumerable reflections of God all around us.

Walking across the street.

Wishing us “have a good day” in the checkout lane.

Passing us on the highway (with opportunities for varying gestures, of course).

When we call someone by name we participate in God’s sacred diversity. Calling someone by their given name allows us to participate in bringing God’s Kindom to life, even if a little bit. When we call someone by name, what we’re saying is we acknowledge that we are all unique expressions and we are choosing to honor theirs. When we call someone by name, we are saying “this is who you were created to be and you have been named by someone who we hope loved and cared for you.”

Yes, this story from Luke’s Gospel is often used to drive home our responsibilities of stewardship, of funding the work we share in bringing God’s Kindom to life through Christ’s church. But at a time when it feels to me like we’re ready to tear one another apart, like we’re losing sight of the human in one another - let alone, the image of God in one another - I’d trade any treasure for a glimpse of a world more willing to call people by name.

A world more willing to say, “I see you.”

A world that understands the faces we condemn on our screens, the groups we assimilate and simplify into expressions of “us” and “them,” the suffering crowds on our screens … each face has a name. Each had someone who cared enough to enter the space to say, “this is how you will be known because I see this in your reflection. I see this reflection of who you are and how you are unique in the world.”

Genesis 1:27 sets the stage for humanity and our relationship with God. The contemporary Message Bible translates it as, “God created human beings; he created them godlike, reflecting God’s nature. He (sic) created them male and female. God blessed them: ‘Prosper! Reproduce! Fill Earth! Take charge!’

We chose Noah’s name because it was Biblical and unique in our family. We have no other Noahs, and really didn’t know any other Noahs. Maybe his name was the reflection of our hopes that he would be different somehow. Maybe we wanted a reversal, a uniqueness in naming our son something that wasn’t common in our lives.

Our uniqueness, our individuality, our diversity is a reflection of God’s beauty and God’s abundance. This is not something we should fear. It is a gift to cherish. Not only do I believe Noah was created to carry that name, I believe Noah was created to be who Noah is, autism and all, by God. He is not a problem to be fixed. When we see one another as projects to fix instead of gifts of connection to God, we reject the wealth of God’s diversity.

Our problems come in efforts to command conformity.

Conformity is an expression of human power gone wrong. Our efforts to achieve conformity in building God’s Kindom have rarely resulted in anything but human suffering. From the papacy using the Crusades to consolidate its power, to the cultural erasure often carried out under missionary movements, to the spiritual trauma left by forced conversions, history shows again and again how attempts to impose a single way of being human have led to deep harm and, ultimately, to failure. Our want for power, our need for others to be like us so that we can feel safe, all say more about us than God or God’s Kindom. Not even the dead rising from the grave can bear enough witness to change our minds.

My son isn’t anyone’s project to fix. And while we have wondered over the years what may have caused Noah’s autism, the truth is I wouldn’t trade the joy of being his dad for one second. Not a dad to a typically-developing child. Not a dad to a boy who collects the same stuff as most boys, like baseball cards or video games. Not a dad to a nice young man with some other form of disability.

I’m Noah’s dad.

The beggar in Jesus’ story experiences wholeness while the rich man who failed to care for him is stripped of his wealth and his privilege. When we allow the myth of conformity to guide how we treat others who are different from us, when we fail to care for those who we keep at arm’s length because they are so very different, we lose out on the reversal of fortune that’s possible when we honor the human in one another. Each of us is a uniquely created child of God whose richness and difference may mean gifts that could be shared for making all our lives better.

Each of us holds a stitch in the seam of social fabric between “us” and “them.” The rich man was able to write off Lazarus in life because he was poor and required to beg. And just like in Jesus’ story, we see people every day who we ask to endure pain so that we remain comfortable. Even though the rich man knew Lazarus as a beggar, when we come to know him by name through Jesus’ story we are able to see how he’s exploited for the comfort of privilege. Being denied the opportunity to exploit someone else comes with the framing of his name - literally, someone who God helped.

When we see the faces of those enduring heartache and pain around us or on our screens, we’d do well to remind ourselves that each has a name. We’d do even better if we take a moment to consider how our comfort keeps them bound.

But we will be totally transformed when we come to see one another as unique reflections of God’s brilliance. It’s a journey of transformation that softens the heart and opens the soul. Noah’s name is synonymous with vacuums for many folks around the world, just like their vacuums are the way he has come to know them. Calling someone by name is the first step in this journey towards love, and it’s quite a trip. It might mean you end up living in a house with 84 vacuum cleaners, but - true to Luke’s Gospel - what a reversal of fortune that journey can be.

Matt, thank you for sharing these beautiful thoughts which helped illuminate the importance of names. And vacuums . 🙂